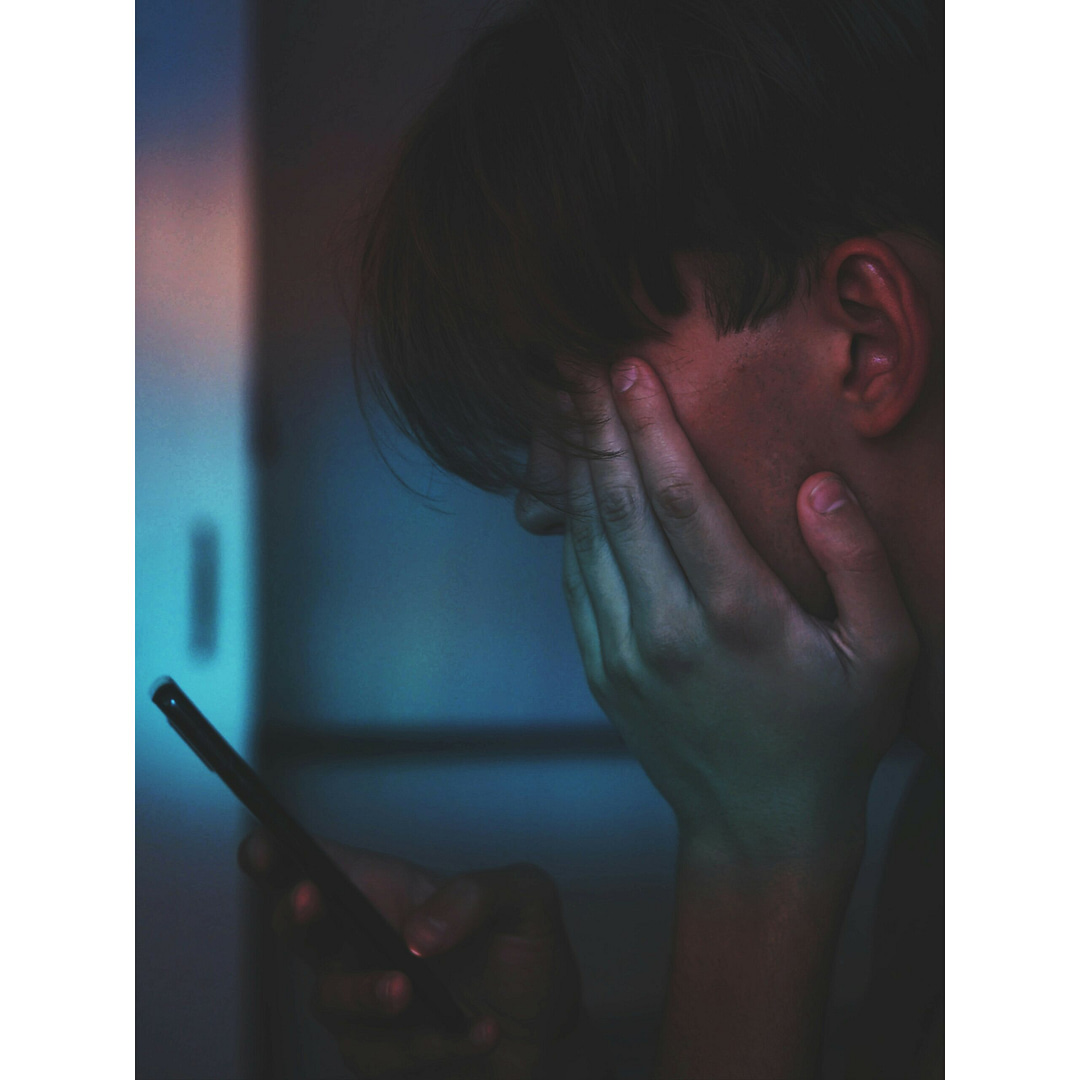

Ek het onlangs ’n nuwe, baie interessante boek van ’n goeie vriend gelees: Dirty Secrets of the Rich and Powerful. Dit is veral die hoofstuk genaamd “Clickbait” wat my bygebly het en net weer laat besef het hoe ’n groot invloed skerms, en veral sosiale media, op ons en ons (groeiende) kinders het! Hierdie platforms word so slim ingespan en ontwerp om ons aandag te hou en ons keuses en aksies te beïnvloed. Geen wonder die ontwerpers en belanghebbendes van dié einste maatskappye laat nie eens hul eie kinders toe om hierdie tegnologieë en toepassings te gebruik nie.

In ons gemeenskap en kringe het die ouers ooreengekom om ons kinders tot ten minste gr.8 van enige slimfone te weerhou, maar ek sien deesdae dat al hoe meer kenners die gebruik van hierdie tegnologie (en veral sosiale media) afraai tot ten minste 16-jarige ouderdom. Ek dink dit is waardevol vir ons as ouers om soveel as moontlik navorsing oor hierdie onderwerp te doen (en bewus te raak van gevare soos afknouery en depressie wat daarmee gepaard gaan), voordat ons hierdie toestelle in ons kinders se hande sit.

Lees gerus hieronder ‘n uittreksel uit James-Brent Styan se boek. Die boek Dirty Secrets of the Rich and Powerful is reeds by meeste boekwinkels op die rakke.

CLICKBAIT

In June 2020, the social media app TikTok overtook YouTube in terms

of the average number of minutes per day that youth aged between four

and 18 years spent accessing its online platform (82 minutes versus YouTube’s

75 minutes). By the end of 2021, kids and teens globally were spending

an average of 91 minutes a day on TikTok compared with just 56 minutes

on YouTube. By 2022, TikTok had more than one billion users, including

135 million in the US alone.

There is no doubt that social media apps are addictive. In a survey conducted

by Common Sense in 2023, adolescent girls in the US admitted to

spending more than two hours a day on TikTok, YouTube and Snapchat,

and more than 90 minutes on Instagram and messaging apps. Nearly half

(45 per cent) of the girls who used TikTok reported feeling ‘addicted’ to the

platform or using it more than intended.

Among all the girls surveyed, 38 per cent reported symptoms of depression,

with 21 per cent indicating mild symptoms and 17 per cent indicating

moderate to severe symptoms. Girls with moderate to severe depressive symptoms

were nearly three times as likely as girls without depressive symptoms

to come across harmful, suicide-related content across platforms at least

monthly. This is because social media apps use sophisticated algorithms to

prolong user engagement. The algorithms guide, sort, match and push content

to users based on their personal interactions, behaviours and interests.

In this case, it is to the users’ detriment, but the algorithm doesn’t care, and

harmful content is particularly profitable.

Platforms such as TikTok, Facebook, Instagram, YouTube and X (formerly

Twitter) make money through advertising. The value of that advertising is

dependent on user engagement. The longer people spend on the platform, the

higher the value. Hence the use of complex, technical algorithms to amplify

content that will maximise time spent on the platform. Harmful content,

like hate speech, disinformation and conspiracies, is particularly engaging,

as it triggers our flight-or-fight instinct, which forces us to pay attention.

Algorithms will therefore amplify this type of content over others …

THE KIDS ARE (NOT) ALL RIGHT

Perhaps more disquieting than the question of what is happening on social

media is the question of who is using these apps. A 2021 survey of American

tweens and teens found that 38 per cent of tweens (aged 8–12 years) and

84 per cent of teens (13–18 years) had used social media. Nearly one in five

(18 per cent) of the tweens said they used social media every day. The survey,

however, defined ‘social media’ as being sites such as Snapchat, Instagram,

Discord, Reddit, Twitter and Facebook; platforms such as YouTube, TikTok

and Twitch were considered online video sites. Looking at the latter, 64 per

cent of tweens and 77 per cent of teens said that they watched online videos

every day. The top four sites among teens were YouTube, TikTok, Snapchat

and Instagram.

A survey in the UK, also conducted in 2021, found that 60 per cent

of 8- to 11-year-olds had their own social media profile. That figure rose to

89 per cent in the 12 to 15 age category and 94 per cent in the 16 to 17

age- category. Thirty-four per cent of 8- to 11-year-olds admitted to having

a TikTok profile, yet the minimum age to open an account on nearly every

social media platform, including TikTok, Instagram, Twitter, Pinterest,

YouTube, Snapchat and Facebook, is 13.

The problem is that few, if any, social media sites use age verification tools.

Any minor can create a profile simply by changing their date of birth. In 2023,

Britain’s Information Commissioner’s Office fined TikTok £12.7 million for

illegally processing the data of 1.4 million children under 13 who were using

its platform without parental consent. The information commissioner said

TikTok had done ‘very little, if anything’ to check who was using the platform

and to remove underage users.

Four years earlier, in 2019, TikTok was fined $5.7 million by the US

Federal Trade Commission for similar practices – improper data collection

from children under 13 – in the US. Compared to TikTok’s annual revenue

of $9.4 billion in 2022, the fines were but drops in the ocean.

The enormous influence wielded by the titans of tech cannot be ignored.

Businesses like Meta (Facebook), Google (YouTube) and ByteDance (TikTok)

will continue harvesting more and more data from more and more people

because data, especially personal data, is valuable. People and governments

need to start understanding the value of their data the way that the tech

giants do …

Styan, James-Brent. “Clickbait.” In Dirty Secrets of the Rich and Powerful. Penguin Random House South Africa, 2024.